Why raise venture capital for your marketplace – and why not

Venture capital is like rocket fuel. It can help your marketplace reach new heights or speed it straight into insolvency. Are you building a marketplace to make a lucrative exit? Get rich? Change the world? Read Sharetribe CEO Juho’s advice on if and when to bring VCs onboard.

Published on

Last updated on

Some marketplace startups need a significant amount of capital to reach their goals.

There are many strategies for a marketplace to acquire this capital. The most popular by far is to exchange equity – shares of your company – for funding.

Many parties might want to buy equity in your marketplace startup. This article focuses on the best-known one: venture capitalists (VCs).

VCs are people who invest money from funds they've raised from other investors called "limited partners." Their goal is to maximize the limited partners' return on investment within a relatively short amount of time.

This makes VCs experts in driving growth and making lucrative exits.

Sometimes, the VC goal is well-aligned with that of a marketplace founder. But even if you wouldn't mind growing fast and getting rich, raising funding from the wrong investors at the wrong time can be detrimental to your business. Investors have pushed many marketplace startups over the edge and into oblivion. At the same time, unicorns like Airbnb would not be where they are today without VCs.

Few decisions in a startup's journey have bigger stakes than those involving venture funding.

So, before getting into how marketplaces can raise VC funding, my first objective is to help you figure out if VC funding is the right option for you. I'll explain how VCs look at the businesses they invest in and list the situations where your goals can match theirs. I'll also reserve a section for equity investors other than VCs: specifically, angel investors and strategic investors.

Investing in early-stage businesses is risky. Nine out of ten startups eventually fail. Venture capitalists exist because more conservative institutions like banks aren’t willing to take those odds. Because the risk is high, VCs also expect high rewards. Let’s examine venture capital incentives with an example: a fund of $100 million.

An average venture capital fund has a lifetime of 10 years. A fund the size of $100 million typically promises its limited partners a minimum return of 3X – a high enough reward for the risks involved in equity funding.

So, our example fund needs to return the limited partners $300 million in 10 years.

VC funds usually focus on a specific funding stage. Traditionally, the first round of venture financing was called Series A, followed by Series B, Series C, etc. At some point, the terms "seed" and "pre-seed" emerged to cover early rounds that happen before the official Series-labeled rounds. The earlier the round, the lower the company's valuation and typical investment size.

Our example fund makes "seed" stage investments in online marketplaces. This is the earliest stage where VCs are involved. An average check is $1M, with a pre-money valuation of $9M, so after investment, the fund owns 10% of the company.

Our fund has an investment period of 5 years, and during that time, it aims to invest in 30 companies, $1M in each. After this period, it won't invest in new companies: the remaining $70 million is reserved for making follow-on investments to the most successful portfolio companies to ensure the fund can keep its 10% share of the company through subsequent financing rounds.

Because of the risk involved in early-stage investments, a successful VC fund that invests in 30 companies typically gets nearly all of its returns from 2–3 companies. So, if our fund wants to hit its target of $300M in 10 years, 2–3 marketplace startups in its portfolio have to reach a valuation of $1B in 10 years to provide enough return on the fund's 10% investment.

This is the part where your VC's incentives can differ dramatically from yours.

Let's say you get an offer to sell your marketplace for $100 million. You might call that a success. Most people would call that a success. But if your company is in the portfolio of our example VC, they'll have a very different viewpoint. They would only net $10M from your sale, which brings them nowhere close to their target of $300M. Our fund would have a strong incentive to prevent such a sale.

The case described above is an extremely simplified example (based on an excellent article on venture capital math by VC Homan Yuen). But it helps in understanding the incentives of venture capitalists and their obsession with "unicorns"– companies that reach a valuation of one billion.

The example also explains why raising VC funding poses such risks for marketplace founders.

Because marketplaces take longer than traditional startups to validate their potential, growing too fast can be detrimental. But from the perspective of a VC, nothing below a "home run" (a unicorn valuation) is very interesting. So, whether your marketplace goes bankrupt or sells for $100M can matter surprisingly little. Cutting corners to maximize growth speed is worth the risk for the VC, even if doing so busts a perfectly viable marketplace business.

With an understanding of how the VC incentives work, let's now look at when raising venture capital can be the right path.

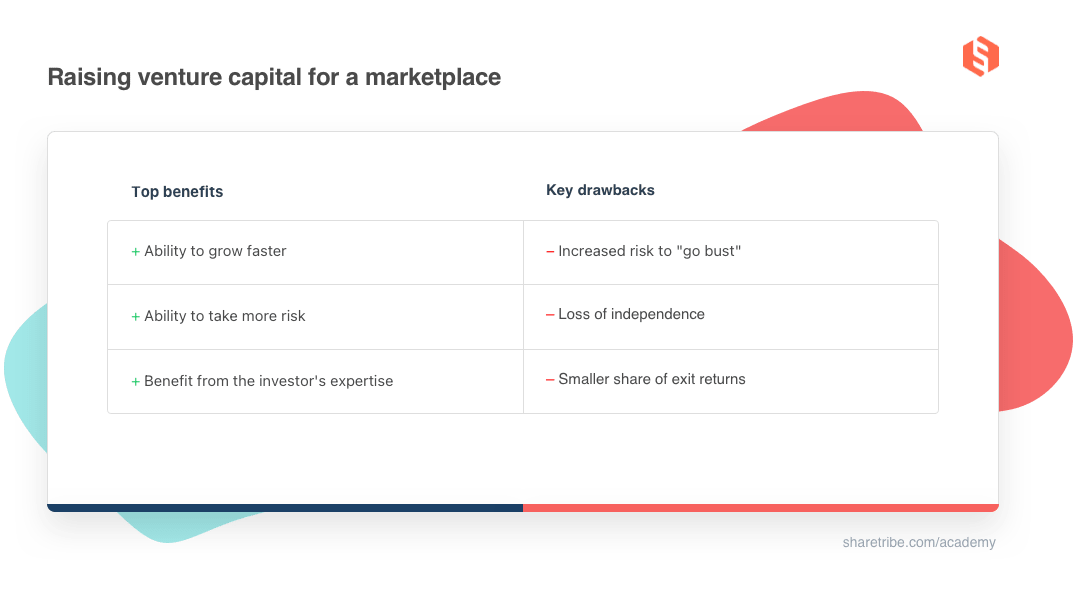

Raising venture capital can be a great decision if your marketplace end goal aligns with your investors' incentives. As we explored in the first article of this series, your marketplace funding options depend on what you want to achieve with your business. Let's examine four common end goals and their compatibility with raising venture capital:

- Building something really big

- Becoming rich

- Making the world a better place

- Building a sustainable business.

Now, it would be easy to say that the first two goals sit well together with VC funding, while the latter don't. But in fact, VC funding can make each goal easier or harder to achieve, depending on the specifics of your business.

Many entrepreneurs are motivated by building a business as big as possible, as fast as possible.

If this describes your motivation well, venture capital might be for you. You probably need a significant amount of money to reach your goal. Your incentives and the incentives of the VCs are perfectly aligned: you both have the "go big or go bust" mindset.

The requirement to build a big business fast might also follow your marketplace concept. Some marketplace businesses operate in "winner-takes-all" or "winner-takes-most" markets, where network effects benefit the biggest player. The window of opportunity in such markets is often limited. Being too early risks facing an immature market, while too late means there's no more room. As a result, you likely face competition from other VC-backed marketplaces. If you don't want to change your concept or narrow your focus, your funding options might be limited to raising capital yourself.

In addition to building a big business, venture capitalists also want to "exit" their investment. There's no way to generate enough return for your VC from your profits. You need to either sell the company or enter the public markets via an Initial Public Offering (IPO).

The latter is typically only viable to companies that generate $100 million per year in revenue or demonstrate strong potential to grow quickly beyond that number. A likelier scenario to make your VC happy is selling your company for a big enough sum. If this is what you want too, your incentives are again aligned, and VC funding is a good option.

Tech press overflows with stories of entrepreneurs who raised VC money and made millions in an exit. But VC funding can make getting rich both easier and harder.

First of all, the VC maths I outlined earlier might block your path to riches. There are many real-life cases where VCs have prevented a sale that would have made the founder extremely wealthy because they haven't been happy with the returns. Instead, the VCs have pushed the company to raise more money to grow bigger, which, in the worst-case scenario, has resulted in the company eventually becoming insolvent and filing for bankruptcy.

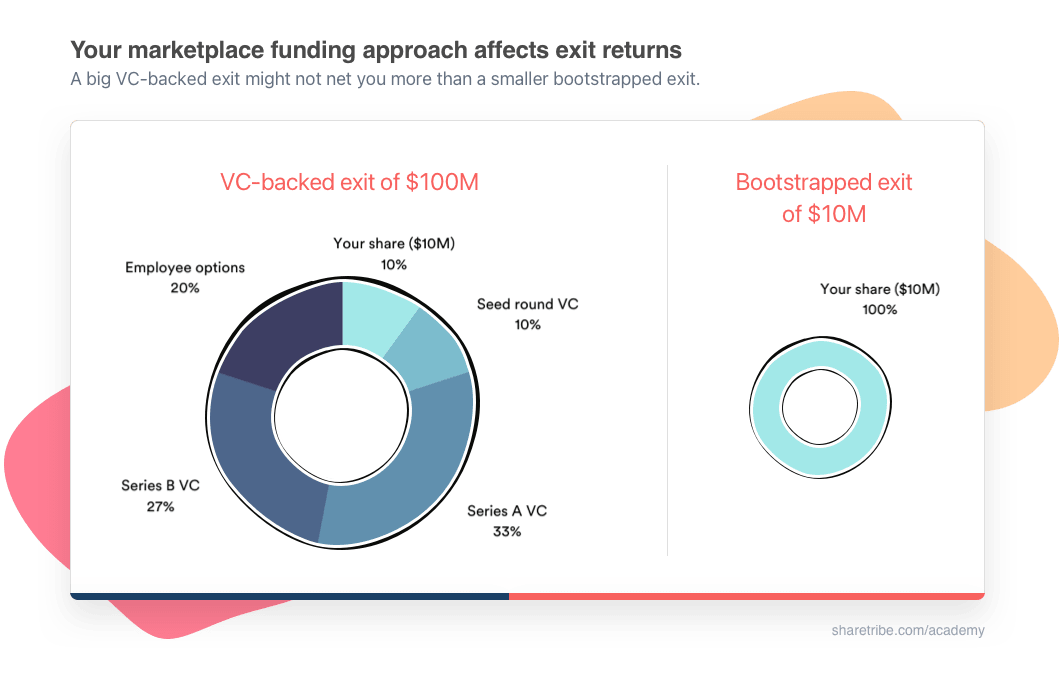

Secondly, even if that $100M sale does go through, you might not receive the returns you expected.

Let's say that after your seed round with our example fund, you raise a $10M Series A round from a different fund with a pre-money valuation of $20M. In addition, your VC requests that you create an option pool of 20% for your team. And our example fund exercises its pro-rata right to participate in the Series A to keep its 10% stake.

This example describes a pretty normal startup funding development. How it plays out is that, once the options have been issued, you only control 37% of your marketplace. If your VC pushes you to do more funding rounds before selling, your portion could be diluted to 10%. In this scenario, a $100M exit only nets you $10M.

It's not likely you could bootstrap your marketplace to a $100M exit. But bootstrapping might bring you to the same $10M result a lot faster.

So, if the goal is to get rich, bootstrapping might be the faster and safer option.

For many entrepreneurs, a social mission is why they started their business in the first place. A marketplace that helps restaurants sell surplus food might have a mission of saving the planet by minimizing food waste. A marketplace that lets people borrow power tools might want to reduce resource consumption by increasing the longevity and utilization of existing assets.

Raising venture capital is a double-edged sword for social enterprises. On the one hand, there certainly are businesses that couldn't deliver on their mission without extensive amounts of money. A good example is companies that tackle immense technical challenges, like helping humans colonize Mars. Such technical challenges are rarely the main reason a marketplace needs upfront capital, but ideas involving significant investments in AI or machine learning could be some exceptions.

On the other hand, raising venture capital can be detrimental to your original mission. For example, let's examine two marketplace success stories: Airbnb and Lyft.

Both companies started with social missions. Airbnb's goal was to put underused rooms to better use; Lyft wanted fewer cars on the city streets.

As these companies grew, their business models ended up having unexpected consequences. Landlords started turning their properties into Airbnb rentals, which led to more vacant spaces, while lower-income residents were pushed further away from city centers as apartment prices went up. Lyft's drivers ended up driving around in the city looking for passengers, many of which chose Lyft instead of public transportation or biking. As a result, Lyft increased congestion.

Airbnb and Lyft could address the problems they caused if they were willing to decrease their revenue. Airbnb could evict professional landlords from its platform. Lyft could limit the number of drivers allowed to be active at any given time.

If their founders and team members controlled these companies, they could consider this option. However, after raising multiple rounds of VC money, both Airbnb and Lyft became effectively controlled by VC companies before going public. It is unlikely that the VCs would have permitted a move that would have been detrimental to its profits. At the same time, Airbnb and Lyft are in markets where "winner-takes-most" applies. Thus, it is unlikely that they could have grown to the size they are today without VC money.

The moral of this story is that you must understand your priorities as a marketplace entrepreneur. Which will you choose if building something huge or creating a positive impact are in conflict?

Today, many VCs profile themselves as impact investors. This doesn't mean they're any less focused on financial return. The main difference is that impact investors consciously narrow their focus by only investing in companies they expect to generate a positive impact. Still, in a scenario where the returns and the mission are at odds, many impact investors also have the fiscal responsibility towards their bosses (the limited partners) to maximize their returns.

To sum up: if a social mission is your main driving force, you should carefully consider whether raising venture capital will end up affecting that mission positively or negatively.

When you raise venture capital, the VCs become your bosses in many ways. The extent to which this happens depends heavily on the exact terms of the investment. (To get to know these terms, I warmly recommend reading Venture Deals by Brad Feld and Jason Mendelson. While some parts of it are specific to US legislation, I think it's a must for anyone considering raising venture capital.)

In any case, raising VC money will mean you have a lot less control over the fate of your marketplace. This is all good as long as your incentives and those of your VC are aligned, but if they differ, it immediately becomes a problem.

For example, you have an opportunity to build a business that operates in a relatively small market. You see a clear path for generating a revenue of $10M and a profit of $1M on an annual basis from this market, and there's very little competition. From your perspective, this could be a great place to be in. However, it's doubtful that VCs would be happy with such a strategy, given the math described earlier.

Venture capital money is rocket fuel, and it's not for every company. The startup world is full of stories where profitable small-to-medium-sized businesses took on venture capital and ended up going insolvent in the pursuit of VC returns. If you're risk-averse or prefer independence and financial sustainability, then venture capital is likely not for you.

If this is the case, you should be honest about it in conversations with potential investors. If you're not striving for an exit that provides venture-style returns, it's not a tenable strategy to claim you are just to raise the VC capital you need.

In addition to venture capitalists, there are other types of investors who provide funding in exchange for equity. The most common are angel investors and strategic investors. They have their own incentives, which sometimes differ from venture capitalists. Again, understanding the motivations of these investor types and ensuring they align with yours is critical.

The main difference between angel investors ("angels" for short) and VCs is that angels invest their own money, and VCs invest someone else's money.

This is a significant difference. A person investing their own money can decide based on a gut feeling. The reason for investing can vary: some angels want to maximize their returns the same way VCs do, while others use their wealth to create a positive impact in the world. VCs focus on finding unicorns and exiting their investment before the lifetime of their fund ends. On the contrary, an angel investor might stay as an investor for the long term and be satisfied with returns from dividends.

Even if you've decided against venture capital, you might still consider bringing in an angel investor, especially if you come across the right person who brings in more than just money. A great example of a valuable angel investor is a serial entrepreneur who has achieved a successful exit and has excellent connections to the investor world. These angel investors have lots of insights on how to scale startup companies.

Many angel investors only invest small sums per company, which means one angel investor might not be enough to reach your funding goal. Thus, raising money from angels can become taxing. You might need to convince many different people to invest in the same round, and they all might have different thoughts on the deal terms.

AngelList, a community site that connects entrepreneurs and investors, introduced syndicates to allow a group of angel investors to pool their investment with one leading angel. Everything Marketplaces, a community for marketplace founders created by Studiotime founder Mike Williams, recently introduced Everything Marketplaces Syndicate, which makes it easy for the community to invest in marketplace startups with individual investment starting from $2,500. This approach is one form of crowdfunding, which I'll look more deeply into in an upcoming article.

Strategic investors are typically large, profitable companies that have put aside some of their profits to create a fund for investing in startups. Instead of purely maximizing their financial return on investment, they typically aim at finding business synergies.

A notable example of a strategic marketplace investment is Toyota investing in the peer-to-peer car-sharing marketplace Getaround. At the same time, Toyota announced a partnership to integrate Getaround's technology into their cars. Similarly, after Electrolux invested in the food waste marketplace Karma, the companies introduced a smart fridge concept for grocery stores.

A strategic investment can work extremely well if the partnership works out. But if it doesn't, the strategic investor can become a liability. What if Karma discovered that the smart fridges wouldn't work and needed to adjust its business model to a direction where Electrolux products are no longer relevant? That might mean a challenging conversation in the boardroom.

Approach strategic investors with caution and ensure you have a plan for what to do if the partnership isn't successful.

The most important lesson for finding the right investors for your marketplace is ensuring that your incentives align with theirs. For some marketplaces, venture capital is a blessing, while for others, it can become a curse. The same goes for other investors, like angel investors and strategic investors.

In the next article, I'll assume that you've read this article and decided that VC is for you. I'll take a deep dive into the strategies that help you successfully raise capital from venture capitalists. In the final two articles of the series, I'll discuss crowdfunding for marketplaces and introduce three non-dilutive funding options: loans, grants, and revenue-based financing.

You might also like...

How to raise venture capital for your marketplace

Sharetribe’s CEO Juho’s complete guide to raising venture capital for your marketplace.

Marketplace funding: The complete guide

Struggling with funding your marketplace? This guide helps you decide how much marketplace funding you need – and when and where to source it.

The top 40 + 10 marketplace investors and VC firms

The title says it all. Here are the people to keep an eye on in the marketplace investment scene.

“Make your marketplace unit economics work,” says Fabrice Grinda

When one of the world’s most successful angel investors talks marketplaces, we listen.

Start your 14-day free trial

Create a marketplace today!

- Launch quickly, without coding

- Extend infinitely

- Scale to any size

No credit card required