Marketplace pricing: How to set the right take rate

The right marketplace pricing level depends on many different factors internal or external to your marketplace. Here's what you should consider to find the optimal pricing level for your marketplace.

Published on

Last updated on

In this chapter of the How to create a marketplace guide, we focus on how to get your marketplace pricing right. Also available as a podcast!

As a marketplace owner, pricing is one of the most important decisions you need to make.

This is especially true when you use the most common marketplace revenue model: commission. What should be the size of your commission (sometimes called "transaction fee", "take rate" or "rake")—the portion of each sale that makes up your revenue?

At first, you might think that the correct answer is "as high as possible". However, as marketplace specialist Bill Gurley of Benchmark Ventures states in his classic blog post A Rake Too Far: Optimal Platform Pricing Strategy, the exact opposite might be true.

There is no single pricing strategy that works for all platforms. In this article, we will go through the most important aspects that affect marketplace pricing and help you choose the correct pricing strategy based on your specific marketplace concept.

Most marketplaces monetize through one or a combination of six marketplace business models:

- Commission

- Membership/subscription fee

- Listing fee

- Lead fee

- Freemium

- Featured listings and ads

By far the most commonly used (and arguably the most lucrative) is commission (or take rate). That's why, throughout this article, I'll use commission as an example.

You can find extensive information on choosing the right model for you in our guide to marketplace pricing models.

The right pricing level differs greatly between marketplaces.

For example, when we studied the business models of the top 100 marketplaces, we found the take rates ranged from a few percent to 95%. But without the context of industry, competition, and marketplace type, this information is not particularly useful.

So, when you determine your marketplace pricing, consider the following eight factors for your marketplace:

- the pricing on other marketplaces

- your marginal costs

- competition

- network effects

- provider differentiation

- transaction size and volume

- quality vs quantity

- who pays the bill.

To get a baseline for marketplace pricing, let's examine what modern marketplaces are doing. On many popular service marketplaces like Uber, Lyft, Fiverr, and Postmates, the commission seems to hover around 20–30%. Some have even claimed that 20% is the optimal commission for most new marketplaces.

Meanwhile, in product marketplaces, the story is quite different. Etsy is on the lower end, charging only 6.5%. eBay and Amazon hover around 10%. Rental marketplaces seem to have more variance, with Airbnb charging around 15% on average and Turo (previously RelayRides) as much as 25%.

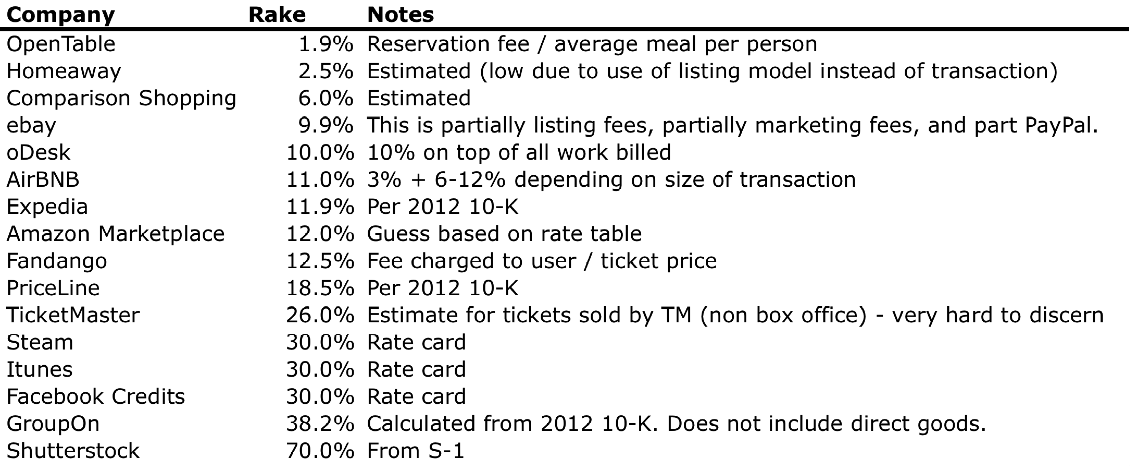

Bill Gurley has made this a handy table for comparing the different take rates of many successful marketplaces. The most important takeaway is that the variations are huge: from OpenTable's 1.9% to ShutterStock's 70%.

Another data point that you might be interested in looking is the data from our top 100 marketplaces study, which you can find in this Airtable, where we found commission rates as high as 95%.

I was curious to find out what pricing strategies people who created their platform with Sharetribe's marketplace software are using. Looking into the data, I found almost 5,000 marketplaces that charge a commission. The average commission on these sites is 9.2%.

Is this a successful strategy? To find it out, I took a look at the 10 most successful Sharetribe customers (in terms of monthly revenue). Their average commission was 12.4%, with the highest being 30% and the lowest 5%. The median was 10%, which was also the most common commission among them. It seems like you can't go too wrong with a 10% commission, and it is likely a good starting point.

Still, as Gurley's table shows, going with the average is too simplified. Several more factors need to be taken into consideration based on your specific type of marketplace business.

The most important thing to consider when thinking about pricing is marginal costs. If your providers already have—even without your marketplace being involved in the equation—very thin profit margins, you cannot expect to take a large chunk of it. A good example is OpenTable, a table booking service with restaurants as providers. Out of each order, most of the money goes towards the salaries of the restaurant personnel, the rent of the restaurant space, the raw ingredients of the meal, and other such costs. The restaurant business is very competitive, so profit margins are very thin. There's not much room for OpenTable to operate in. The same goes for Etsy: the seller needs to buy the material, manufacture the item, and ship it to the buyer. There are lots of sellers out there, so competition is fierce, and profit margins are low.

Meanwhile, the stock photo market is very different (as are digital goods markets in general). Once you've produced a digital product, you can sell it an unlimited number of times for no extra cost. 30% of the sale price is pure profit for the photographer every time they make a sale.

If your marketplace sells lots of different types of products that have great variety in their marginal costs, you might want to consider different commission rates for different product categories. Typical examples of well-known marketplaces that do this are eBay and Amazon. Amazon's fees range from 6% to 45% based on the category of the product.

Another factor to consider is the different channels through which your providers currently distribute their products or services. Are you their only channel? This might be the case if you manage to find a narrow enough niche that nobody else is catering to (yet). With a monopoly on a niche, you will likely be able to charge more for operating the marketplace. This is another good reason to have narrow focus, especially in the beginning.

However, a more likely scenario is that other channels exist, and you need to create a competitive offering. Restaurants had customers coming in through various channels when OpenTable started—some of which cost the restaurants nothing!—so the table-booking service needed to have extremely competitive pricing.

Etsy faced a similar situation when it started: many of its sellers were already selling on Amazon or eBay. By setting its fees to only 50% of what its competitors were charging, Etsy positioned itself as an attractive option for sellers. While Etsy likes to claim that it's better than the alternatives in many other ways as well, the pricing strategy definitely helped it carve market share from big competitors—especially in the early days. Etsy has always stressed that it can only succeed if its sellers succeed with their businesses, and a low take rate communicates this viewpoint effectively.

While Etsy's fees are currently quite low, it is facing a lot of pressure. Etsy is a public company, and its shareholders are demanding higher profits, creating pressure to increase commission rates. There might still be an opportunity for competition to take on Etsy. By focusing on a smaller segment, crafting a good value proposition for your providers, and charging lower fees, you might well be able to disrupt Etsy. As Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, famously said: "Your margin is my opportunity."

A great example of how lower marketplace pricing can be used to disrupt a market leader is how TaoBao beat eBay in China. If you are competing with a market leader like eBay and Etsy by trying to attract their providers to your platform, you either need to provide more value for your customers and providers, or charge lower fees.

Photographers don't have good alternatives to large stock photo sites if they want to sell their photographs to large masses. This is why the sites can charge large commissions. Selling photos through a physical retail shop or their own online store is much less effective. However, Shutterstock and other stock photo sites (such as Getty Images, which charges an even higher commission of 80%) are facing tough competition as the cost of building a marketplace business is going down, and new competition is emerging. Stocksy, a new stock photo site owned by the photographers themselves, has been acquiring photographers from bigger competitors with its lower fee. There are lots of opportunities for newcomers in the fat margins of big players.

A factor that is closely related to the number of distribution channels is the network effect. A marketplace benefits from network effects if having more providers makes the marketplace more valuable for customers. This is an important reason why stock photo sites have been able to keep their commissions high. A stock photo site becomes infinitely more useful to a customer when its selection increases, especially since each offering on the site is unique. Also, since stock photos are generally needed for very specific topics, customers will flock to the platforms with the widest selections.

On the surface, it might seem that all marketplaces benefit from the network effect. To some extent, this is true. However, especially in the field of local and non-unique services, there can be a cap to this benefit. A good example is on-demand ridesharing, where Lyft has been able to successfully carve market share from Uber, a much bigger and better-funded competitor. As Lyft's CEO John Zimmer explains: "Once you hit three-minute pickup times, there's no benefit to having more people on the network." In the same article, W. Brian Arthur, a theoretician behind network effects, notes that if all the provided services on a marketplace are (nearly) identical, network effects may not be so advantageous. If the marketplace can always meet the needs of a customer with a given set of providers, there's no additional benefit in increasing the number of providers.

In general, the stronger the benefit from the network effect, the higher your commission can be—as long as your network is big enough. The closer you are to having perfect competition, the less benefit you get from the network.

In the real world, most marketplaces are far from perfect competition. There are often various types of providers: some are professionals with multiple daily transactions, while others might only make a sale once or twice a year. This poses an interesting pricing question: should you have the same pricing for all providers?

Different marketplaces have taken different strategies for this. eBay offers benefits to people who sell a lot: while the base fee is not lower, power sellers enjoy cheaper shipping, unpaid item protection and promotional offers. Airbnb offers its superhosts perks like travel coupons and priority support. The reasoning behind these programs is clearly to encourage people to sell more and to retain the most successful providers on the platform.

Etsy has taken a different strategy. It offers paid premium services such as direct checkout, shipping labels and promoted listings. These services are specifically targeted towards the platform's premium sellers. Marketplace specialist Boris Wertz calls this the freemium model for marketplace pricing. Wertz explains the rationale: "By relying less on monetizing the smaller sellers, the platform ensures that these small sellers can afford to stay on the platform and contribute their crafty and unique inventory that Etsy buyers want. Etsy then takes a higher rate from the big sellers that can most afford it due to their scale."

Bill Gurley mentions that Booking.com used the same approach. It first took over the market with low pricing, but then started offering paid promotion services that increased take rates. Gurley notes: "When prices go up due to bidding and competition, the suppliers blame their competition, not the platform."

Pricing is all about psychology. The one figure your providers really care about is the amount of money you're extracting from each transaction. If they perceive it to be high, they will become suspicious.

Providers' suspicion does not necessarily directly correlate with commission percentage. The bigger the total size of a transaction, the smaller the expected percentage. In general, people perceive the marketplace to provide certain value by facilitating a transaction, and quite often people feel that the facilitation of two transactions worth $50 each was more valuable than facilitating one transaction worth $100. After all, the marketplace did more work for them there. Fiverr charges a 20% commission, but since a typical transaction size is only $5, it doesn't sound that big: it's only $1 per transaction, after all.

If transaction sizes vary a lot in your marketplace, you need to consider whether having the same fee for all transactions makes sense or not. Airbnb's rates for guests vary from 6 to 12 percent based on the size of the total transaction. The higher the total sum, the lower the commission. This way Airbnb encourages customers to make bigger purchases.

As a founder, you need to build a sustainable business model for your marketplace by evaluating your market closely: how many potential transactions can you expect to get in a month, and what do you expect the total transaction size to be? I suggest doing a little spreadsheet exercise by playing around with the different variables to find the optimal price point for your marketplace.

If you feel that your market is huge, you will probably have more competition. This also means that you will likely need to keep your pricing low. This does not necessarily mean low profits, however. Gurley quotes the famous business educator Peter Drucker: "The worship of premium pricing always creates a market for the competitor. And high profit margins do not equal maximum profits."

As you learned from the previous guide chapter on marketplace leakage, the key to keeping transactions in your platform is to provide as much value as possible for both sides of your marketplace. The amount of value provided naturally correlates strongly with your pricing. If you provide more value, the perceived quality of your offering is higher, which justifies higher prices. The better you are at communicating the high quality of your offering to your customers, the easier it is to charge more.

A good example of how to provide additional value—and thus increase quality—is with insurance for rental marketplaces. If the marketplace is insuring the rented item, it is easy for both the provider and the customer to accept the cost related to the transaction. They can clearly see what they are getting for the fee.

Vetting providers is another common way to enhance quality. While some marketplaces let anyone become a provider, others curate the onboarding carefully, hand-picking each provider and possibly conducting a background check, or giving the customers the tools to do so. This is especially important in quality-intensive marketplaces such as dog boarding, babysitting, or taking care of the elderly. Stock photo site Stocksy is using the vetting strategy effectively to disrupt the stock photo market.

You need to decide whether you want to focus on quantity—getting many providers to increase your selection—or quality—curating your selection carefully. In the latter case, your pricing should likely be higher to communicate the value you provide, whereas in the former case you need to keep your margins low to get as many people on board as possible.

Sometimes both of these strategies can be applied to the same market. For instance, EatWith, a marketplace for home-cooked meals, has been very careful in curating the providers based on their culinary skills. Meanwhile, their competitor VizEat has chosen to allow anyone to become a provider. EatWith has positioned itself as the premium option, with higher fees, while VizEat relies on its wide selection. Time will tell which approach works best. So far, EatWith seems to have the upper hand in terms of funding and brand awareness.

Since marketplaces have two sides—the customer and the provider—an important consideration is which party pays the bill. In practice, both mean the same thing: the money is split between you and your provider. However, for psychological reasons, how you communicate this can make a big difference.

As investor Fabrice Grinda notes, most marketplaces are demand-constrained: once there are enough customers, the providers will flock to the marketplace. Some sharing economy marketplaces like Airbnb can also be supply-constrained, especially in the beginning: it can be tricky to convince people to rent their houses out to strangers, so the limiting factor is supply.

As Bill Gurley states, "you want to build a platform that has the least amount of friction (both product and pricing). High rakes are a form of friction". In general, you want to lower the friction for the side that you are constrained with. That is why eBay and OpenTable charge the providers, but Airbnb places most of the fees on the guests. It uses a system where the guest pays between 6% and 12% of the transaction price and the host pays 3%.

In the classical Harvard Business Review article on marketplace dynamics, Strategies for Two-Sided Markets, the authors argue that in some cases, it even makes sense for the platform to subsidize the most price-sensitive side to reduce friction and capture market share. This tactic has recently been employed by Uber, which slashed its pricing due to increased competition, and tried to prevent the backlash from drivers by paying them more than they "earned". Naturally, this strategy requires a lot of capital to work.

As we've seen, there are a number of factors that affect the pricing decision. As a simple framework, I present the following: start from 10% and then look into how your marketplace is positioned in terms of the seven factors mentioned in this article (marginal costs, distribution channels, network effect, provider differentiation, transaction size, and volume, quality vs quantity, and who pays the bill). Based on that analysis, adjust the percentage.

In general, you should take as little as you need to remain sustainable. As Bill Gurley states: "High rakes are a form of friction precisely because your rake becomes part of the landed price for the consumer. If you charge an excessive rake, the pricing of items in your marketplace is now unnaturally high (relative to anything outside your marketplace). For your platform to be the 'definitive' place to transact, you want industry-leading pricing—which is impossible if your rake is the de facto cause of excessive pricing. High rakes also create a natural impetus for suppliers to look elsewhere, which endangers sustainability."

Remember that it's ok to change pricing, and you probably should iterate on it as you go. However, it's always difficult to raise prices, so starting off with a higher price and then reducing it if needed is probably a better strategy than the other way around. If you wish to get more supply in the beginning by offering cheaper pricing—which is often a good idea—you should consider offering time-based discounts ("first 6 months with 50% discount on fees!"). It is important to clearly communicate that pricing will return to normal levels after the initial discount period.

You might also like...

How to validate your marketplace idea before building the platform

Don’t build a desert platform. Here are the steps to take to prevalidate your marketplace idea.

How to build your marketplace supply

How to bring in the first, quality providers before your platform has any customers.

How to turn your marketplace into a community

Engage your best providers by turning them from users into community members.

Marketplace funding: The complete guide

Struggling with funding your marketplace? This guide helps you decide how much marketplace funding you need – and when and where to source it.

Start your 14-day free trial

Create a marketplace today!

- Launch quickly, without coding

- Extend infinitely

- Scale to any size

No credit card required